Cameroon The Country That Votes But Power Never Changes

Cameroon goes to the polls today not to choose a president, but to rehearse its captivity. At 92, Paul Biya, Africa’s oldest ruler and the continent’s most enduring ghost of power, stands ready to claim a new mandate in a nation that long stopped believing in elections. For 43 years, he has ruled not by inspiration but by inertia, turning the state into a monument of decay where corruption thrives, hope shrinks, and apathy has become a national instinct. Yet somewhere amid the fatigue, a spark has flared: Issa Tchiroma Bakary, the defector draped in yellow, now rides a wave of popular anger that could, if courage endures, mark either Cameroon’s awakening, or its final surrender.

POLITICS

E. N. Quenti

10/11/20255 min read

YAOUNDÉ — Cameroon votes today, but few believe the outcome will surprise. At 92, Paul Biya, the world’s oldest and longest-serving elected leader, stands poised to claim an eighth term in office, extending his 43-year rule until the age of 99. The ballot, for many, feels less like a choice than a ritual of submission.

What unfolds across the country today is not democracy in action but democracy in costume: an elaborate performance choreographed to legitimize what has long been decided. ELECAM, the electoral commission that answers upward rather than outward, will count the votes. It will declare victory. And the president, who has ruled since Jimmy Carter was in the White House and Emmanuel Macron the current French president serving his second term was four years old, will smile from behind dark glasses, unbothered by time or truth. Yet beneath the managed calm, something stirs.

The yellow wave

In recent weeks, a movement that no one quite saw coming has swept across the north and spilled into the cities. Issa Tchiroma Bakary, the former loyalist turned challenger, has drawn enormous crowds draped in yellow, chanting for “transition.” It is a remarkable twist of fate: the regime’s longtime spokesman, now its most visible opponent.

Born in 1949, Tchiroma has lived the system from within. He served as Biya’s Minister of Employment, then as government spokesman, the voice that once justified the injustices Cameroonians endured. But in June, he broke ranks, declaring that the country “can no longer be ruled by one man’s will.” His platform, decentralisation, anti-corruption, youth empowerment, reconciliation in the Anglophone regions, reads like an apology letter to the nation he once helped deceive.

His rallies have been vast, defiant, almost surreal in a country accustomed to muted dissent. In Maroua, crowds shut down traffic for hours. In Yaoundé, the yellow banners multiplied faster than police could tear them down. Heavyweights like human rights lawyer Felix Agbor Balla and veteran journalist Eric Chinje have publicly endorsed him, lending the movement moral weight and credibility.

For the first time in decades, Cameroonians have begun to imagine what a post-Biya future might look like.

Between redemption and repetition

Still, Tchiroma’s rise poses as many questions as it answers. Is he truly transformed, or simply opportunistic? Can a man who once defended corruption now dismantle it? His critics call him a chameleon; his supporters, a prodigal son.

What’s certain is that his campaign has broken Biya’s monopoly on energy and imagination. The ruling party’s own rallies, padded with civil servants and scripted enthusiasm, have paled beside the raw passion of Tchiroma’s supporters. The “yellow wave,” as it’s been dubbed, carries echoes of the 1992 and 2018 elections, both times the opposition won the streets but lost the count.

And that may well repeat. Even if Tchiroma secures the popular vote, ELECAM will almost certainly deliver the presidency to Biya, as it has done before. Then will come the real test.

After the count

What happens when the numbers are announced? Will Cameroonians take to the streets? Will Tchiroma call them there? History suggests otherwise. Biya has survived coups, strikes, and international pressure because he understands one truth: Cameroon fears chaos more than it desires change.

The regime has always known how to neutralize its rivals, not with prisons alone, but with positions. When the results come in, Biya will likely extend his hand: a ministerial post, perhaps, or a “national unity” role. The same script that tamed past challengers may yet ensnare Tchiroma.

Will he refuse? Will he hold the line? Or will the yellow wave recede into the old swamp of accommodation and betrayal?

A nation adrift

Cameroon once stood as a model of promise, a bridge between cultures, a nation with fertile land, bright minds, and patient pride. Today it trails its neighbours in nearly every measure that matters.

Benin and Côte d’Ivoire surge ahead in governance and growth. Rwanda, rebuilt from ashes, has become a magnet for investment. Even oil-rich Equatorial Guinea boasts infrastructure Cameroon can only envy. Meanwhile, nearly 40% of Cameroonians live in poverty. Hospitals run out of drugs. Courts sell verdicts. Schools crumble. Youth unemployment hovers around 40%, forcing thousands to flee abroad in search of dignity.

This election, then, is about more than who sits in Etoudi Palace. It is about whether Cameroonians still believe their choices count for anything at all.

No easy way out

Let’s be clear: freedom will not be gifted by decree. Biya will not simply age out of power; regimes like his end only when people refuse to be ruled by fear.

If Tchiroma’s movement is to mean anything, it cannot stop at the ballot box. The real work, the dangerous work, begins after the announcement. It will demand sacrifice: strikes, civic defiance, the courage to face the state’s batons and tear gas. Without that, the yellow wave will fade like so many before it, remembered briefly, then buried under the weight of resignation. Cameroon’s tragedy has never been its dictator alone. It’s the silence that made him possible.

The dawn or the dusk

Today, as Cameroonians line up to vote, the choice is not merely between Biya and Tchiroma. It’s between submission and self-respect. Between a future fought for and a past prolonged.

Tchiroma’s yellow wave may crash against the walls of Biya’s iron rule, but it has already done something the regime cannot undo: it has reminded Cameroonians that the emperor bleeds, that the spell of inevitability can break.

The question is whether the people will keep pushing once the ballots are counted, once ELECAM announces the predictable, once the world looks away. Because no saviour is coming, not from Paris, not from Washington, not even from Garoua.

The dawn, if it comes, will not be granted. It must be taken.

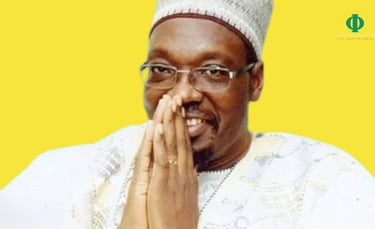

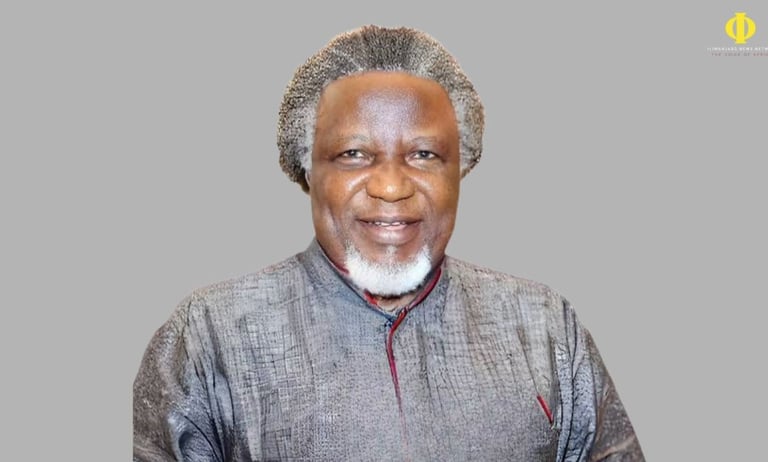

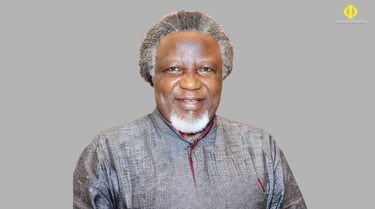

Veteran Journalist Eric Chinje

Large Crowd at Tchiroma campaigns

Human rights lawyer Felix Agbor Balla.

Issa Tchiroma Bakary Front Runner