The Grand Return: Egypt and Nigeria Raise New Museums to Reclaim Africa’s Stolen Memory

For centuries, the greatest heist in human history was not treated as a crime. It was curated. Our royal regalia, our sacred icons, the very archives of our civilisations, were placed behind glass in foreign museums, labeled with the names of the thieves. Our story was stolen, and with it, our pride. But now, from Cairo to Benin City, the keys to those glass cases are finally, triumphantly, coming home. A stolen chapter cannot tell the whole story. For too long, the book of human civilisation was missing its foundational volume: Africa. The narrative was twisted, claiming the light of progress only arrived on our shores with colonisers. But today, that missing chapter is being restored, not with ink, but with the gleaming bronze of returned artefacts and the monumental ambition of two new museums that stand as defiant correctors of the historical record.

ART AND CULTURE

E. N. Quenti

11/16/20253 min read

For centuries, the story of human civilisation has been told with a glaring, deliberate omission. Africa, the cradle of humanity, has been airbrushed from its own masterpiece. Our wealth was stolen, our cultures were plundered, and most insidiously, our history was hijacked. We were taught a lie: that civilisation was a light brought to a dark continent by European arrivals. This was not just an error; it was a weapon of psychological conquest.

But today, from the sands of Cairo to the heart of Benin City, a powerful, long-overdue renaissance is underway. Africa is not just asking for its story back; it is building magnificent new chapters to house it. The opening of the $1.2 billion Egypt’s Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM) and Nigeria’s spectacular $25 million Edo Museum of West Africa (EMOWAA) are not merely architectural projects. They are acts of intellectual and cultural liberation, a full-throated declaration that Africans are seizing control of their own narrative.

First, consider the scale of the reclamation. The GEM, poised at the foot of the Giza Plateau, is not just a museum; it is a statement in glass and stone. It will be the largest archaeological museum complex in the world, a custodian for over 50,000 artefacts, including the entirety of Tutankhamun’s treasures displayed together for the first time. This is a celebration of a civilisation that, for over 3,000 years, was the unrivalled apex of human achievement. It was a society that mastered mathematics to build monuments that defy modern engineering, that pioneered medicine, developed a written language when Europe was in its infancy, and laid the foundational stones for astronomy, architecture, and statecraft that the world still benefits from today.

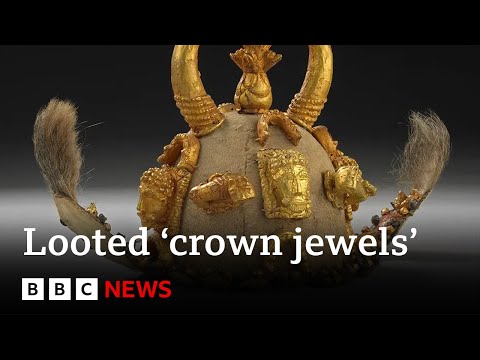

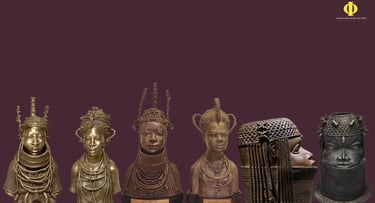

Simultaneously, in Nigeria, the EMOWAA project represents a different, but equally vital, form of reclamation. It is a direct response to one of history's most brazen acts of cultural theft: the 1897 British Punitive Expedition that looted thousands of the Benin Bronzes. These are not mere artefacts; they are the courtly archives of the Kingdom of Benin, cast in metal with a sophistication that stunned the very Europeans who stole them. The Bronzes depict kings, queens, rituals, and daily life, proving the existence of a complex, advanced, and powerful African society centuries before colonial contact.

For decades, these masterpieces were held in museums in London, Berlin, and New York, their labels telling a story filtered through a colonial lens. Their return to Nigeria, to be housed in a world-class museum designed by Ghanaian architect David Adjaye, is a monumental victory. It is the literal and symbolic return of a people’s soul, their history, and their right to tell their own story.

The lie we must now systematically dismantle is the myth of the "uncivilised" Africa. The truth is that while Rome rose and fell, the Nile Valley civilisations were ancient. While Europe endured its Dark Ages, the empires of West Africa Ghana, Mali, and Benin were thriving centres of trade, learning, and art, their wealth and sophistication documented by Arab scholars and later ignored by European ones. Africa’s civilisational run is the longest and, for millennia, the most dominant on the planet.

The GEM and EMOWAA are the physical rebuttals to this twisted narrative. They are institutions built by Africans, for Africans, and for the world, to proclaim a simple, powerful truth: we do not need others to validate our history. We are the descendants of the architects of pyramids, the founders of philosophy and science, the creators of art that captures the very essence of humanity.

This is more than a cultural moment; it is an educational imperative. Our children must no longer be taught that their history began with the chains of slavery or the borders of colonialism. They must learn of the 3,000-year reign of the Pharaohs, of the University of Timbuktu, of the astronomical knowledge of the Dogon, and the metalworking genius of the Benin brass casters.

The grand return of our artefacts is the grand return of our pride, our identity, and our agency. It is the understanding that our past is not one of darkness waiting for a foreign light, but a brilliant sun that illuminated the world. We are now, rightfully, reclaiming its rays. The narrative is ours again, and we will tell it in our own voice, from our own soil, for generations to come.

The Grand Eyptian Museum

The Benin Bronzes

Ghana Loaned Back its Own Crown Jewels Looted By The British